A copy of a paper I wrote for a class I took called “Mediating Disaster: Fukushima Before and After” that focused on themes of loss, memory, and trauma in the wake of disaster. Writing for someone who never watched the series proved difficult, and I felt like I didn’t go into as much depth as I wanted to. Nonetheless, I hope you all enjoy reading my thoughts about Mawaru Penguindrum and how it relates to post-3/11 Japan.

In recent times, the use of the word “hope” (希望, kibou) has escalated in both mass media and popular culture. The number of times the phrases “you are our only hope” or “you are our last hope” have been recycled feels limitless and the word has almost been reduced to the status of a cliché. There’s another word that I feel coincides with many of the emotions and shades of meaning associated with “hope,” and that word is “fate” (運命, unmei). Similar to “hope,” “fate” is a word that is always pointing towards the future and is always concerned about a destination, occupying both temporal and spacial connotations.

It’s an interesting and complex word that is immediately problematized from the very opening moments of Mawaru Penguindrum, an original TV anime series released in the wake of the March 11th tsunami disaster in Japan. The director, Kunihiko Ikuhara, is well-known for his work as an episode director for the original Bishoujo Senshi Sērāmūn (Sailor Moon, 1992) as well as directing the anime adaptation of Shoujo Kakumei Utena (Revolutionary Girl Utena, 1997). Mawaru Penguindrum began airing in early July of 2011, running for two cours, and is framed by disaster. The story itself centers around three siblings, Kanba, Shouma, and Himari Takakura, and the first episode begins with a monologue from Shouma in which he says:

“I hate the word ‘fate.’ Birth, encounters, partings, success and failure, fortune and misfortune in life. If everything is already set in stone by fate, then why are we even born? There are those born wealthy, those born of beautiful mothers, and those born into war or poverty. If everything is caused by fate, then God must be incredibly unfair and cruel. Because, ever since that day, none of us had a future. The only thing we knew was that we would never amount to anything.”

Here, Shouma offers a pessimistic and troubled perspective of the word “fate.” He believes that the word binds us to a preset track that is generated and determined at a specific point in time. For the Takakura siblings, that specific moment is “that day” that he mentions. It’s an ambiguous quote that could refer to the day each sibling is born, but it could also refer to any of the various tragedies that each sibling experiences throughout their lives. In relation to the events of the first episode, “that day” refers to the day that the Shouma and Kanba discovered that their sister Himari was diagnosed with a terminal illness. Upon receiving the news from the doctor, Kanba denounces God and says that he must not even exist if something like this is allowed to happen. The use of the word “fate” here implies a forward motion through time against one’s will, carrying with it shades of hopelessness.

While the first episode proposes this negative view of “fate,” the series subsequently challenges this argument when we’re introduced to the fourth main character Ringo Oginome in the beginning of the second episode, opening with a monologue that parallels Shouma’s in the first episode that reads:

“I love the word ‘fate.’ You know how they talk about ‘fated encounters?’ Just one single encounter can completely change your life. Such special encounters are not coincidences. They’re definitely ‘fate.’ Of course, life is not all happy encounters. There are many painful, sad predicaments. It’s hard to accept that misfortunes beyond your control are fate. But I think…there’s a meaning no matter how sad and painful things may be. Nothing in this world is meaningless. Because…I believe in fate.”

This interpretation of the word “fate” here reads more closely to the traditional meaning that “hope” embodies, which requires an acceptance of the circumstances at hand and a belief that everything, from happy events to disasters, happens for a reason. Ringo seems to suggest that life is a conglomeration of this fortune and misfortune and that the natural order of things and the sum of these events are what make us human. In this way, “fate” becomes a tool that can be used to accept misfortune, and even tragedy, as well as to grow out of it.

According to Anne Allison’s chapter “Hope and Hope” from her book Precarious Japan, Shouma’s negative of view concerning “fate” and predestination is a sentiment that appears to be shared with much of Japanese youth today[1]. In the face of an economic downturn beginning in 1991 (20 years before the airing of Mawaru Penguindrum), the feeling that they will “never amount to anything” has led an entire generation to a lack of drive and a retreat inward both mentally and physically, fueling the hikikomori and NEET phenomenon, as well as attributing to Japan’s social and economic precarity. These images of social withdrawal coincide with the heavy use of box imagery in Mawaru Penguindrum. In the penultimate episode’s opening, the main antagonist Sanetoshi Watase reveals that he plans to repeat a terrorist attack that occurred 16 years ago and says:

“This world is made of countless boxes. People bend and stuff their bodies into their own boxes. And stay there for the rest of their lives. And inside the box, they eventually forget: What they looked like. What they loved; who they loved. That’s why I’m getting out of my box.”

With this social withdrawal, he draws the connection from the box imagery to the loss of identity and purpose. Believing that people have become more preoccupied with themselves and their personal “boxes,” he decides that cleansing Tokyo in fire will liberate the city. Appropriately, his method involves a large number of explosives concealed in boxes throughout Tokyo’s rail system. While it’s never directed stated in the anime, the terrorist event that is continually mentioned is a bold allusion to the 1995 Sarin gas attacks in Tokyo.

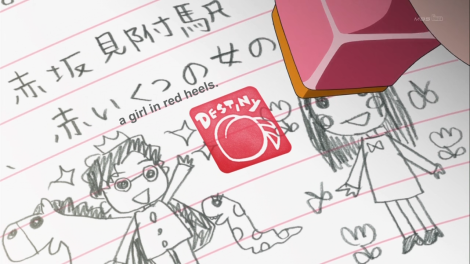

Trains play an important role in Mawaru Penguindrum, not only as an allusion to the Sarin attacks but also for their ability to merge the concept of social boxes with the motion of fate. They’re devices that are designed to house us in boxes and transport us to our desired destination along designated tracks. This is made evident in the series by the train motif that is used when scenes transition to different locations or when flashbacks occur. These transitions are always accompanied with a Tokyo subway style destination sign indicating where or when the next scene is going to take place. Some scenes occur in an abstract location known as “The Destination of Fate” (運命の至る場所, unmei no itaru basho). This location takes the form of a subway cabin, often with strange color palettes and the number 95 can be seen projected throughout the train, a reference to the Sarin attacks. Each 95 is inscribed by a circle of arrows to represent the constant motion that is brought about by fate and perhaps even disaster itself.

Just as Sanetoshi suggests with his desire to get out of his box, the struggle to rebel against one’s fate is a theme that is greatly explored in Mawaru Penguindrum. Anne Allison throws this uncertainty into question and asks, “how does one generate hopefulness about oneself in the first place and is it only from the shelter of a certain kind of my-home-ism…?” In Mawaru Penguindrum, imagery of birds is juxtaposed with cute penguin mascot characters that appear to serve little purpose outside of being simply eye candy. However, I believe that penguins are the very embodiment of rebelling against fate. Unlike most other birds, penguins have been stripped of the ability to fly. However, through evolution they’re able to find a means of survival through swimming in the water. As with the other major themes in the series, the idea is introduced through a monologue. This particular idea is first alluded to at the end of the first episode, with Kanba saying:

“Why are people born? If we were created only to suffer, is it meant as some kind of a punishment? Or a cynical joke? If that’s the case, animals that adhere to the survival strategy programmed to their DNA are far more elegant and simple. If there really is an existence worthy of being called ‘God,’ I want to ask him one thing. Is there really fate in the universe? If a man ignored his fate, his instincts, and his DNA’s commands to love someone…is he really human?”

In a similar vein to Shouma’s critical thoughts about fate, Kanba questions what the more “human” course of action is. Is it to simply adhere to what circumstances have been presented to us, or should we take active control to get what we desire? Kanba seems to be insisting that we need to find our own “survival strategy” (生存戦略, seizon senryaku) to avoid being caged birds and that humans are capable of shaping their own destinies.

Inherited issues and the construct of the home are important points of discussion regarding modern Japan, and these points are represented in very abstract ways in Mawaru Penguindrum. Late in the series, we learn that the three Takakura siblings are actually not blood related and were brought together by fate at different points in their lives. The encounter between Shouma and Kanba is depicted with a scene of the two trapped in adjacent cages located in a black void. The two are on the verge of starving to death when fate intervenes by providing Kanba the means to survive, in the form of an apple. Despite being chosen by fate, Kanba willing shares part of the fruit with Shouma, allowing both of them to survive. Shortly after this meeting, Shouma finds Himari abandoned in a bleak warehouse called “The Child Broiler” (こどもブロイラー, kodomo buroira) where unwanted children are disposed of, and saves her by sharing a part of his apple.

From this point on, they live together under the same roof and put on a charade of a family unit that even fools the viewers for the first half of the series. The Takakura household is the most vibrant setting in the entire series, contrasting heavily with the many other abstract and sometimes monochromatic locales. Much detail is given to scenes that take place in the house, as if to highlight the importance of the concept of home. Primary colors dominate much of the palette, lending childlike innocence that masks the façade of three children who are simply playing house.

In the final episode, it’s revealed that the apple that was shared between the three is the titular Penguindrum. This fruit granted each of them life in the face of death, and as punishment, fate afflicted Himari with her terminal illness. To save Himari and prevent Sanetoshi’s attack on Tokyo, the brothers initiate the “Survival Strategy,” a spell that requires that they return each piece of the Penguindrum to Himari to “transfer fate.” At the cost of their lives, they’re able to reject the predestined path that they were dealt and divert the course of fate onto another track, one in which they were never born and Himari was never ill.

Recalling Anne Allison’s question about how to “generate hopefulness about oneself,” we see that the Takakuras generate hope out of the desire to change their own fate and the desire to create a better future, regardless of what obstacles there may be. Like the metaphor with the penguin mascots, the Takakuras forge a way to transfer their fate through unconventional and unscripted methods, such as sharing the fruit of fate and initiating the “Survival Strategy.” They even create an idealized home for themselves that acts as a shared sanctuary, what Anne Allison might refer to as “my-home-ism.”

Mawaru Penguindrum offers many different views concerning the word “fate” and abstracts it as a multi-faceted concept. There’s uncertainty attached to the word, and it carries a deep connection to the precarity hovering around today’s Japan. However, it’s made clear by the end of the series that if one wishes to change fate, action is required. It seems that the series agrees with the opinions of the brothers that fate is something that must be opposed to get what you want, but almost surprisingly the series ends with Himari saying, “I love the word ‘fate’.” The director Kunihiko Ikuhara mentioned in an interview (translated and posted on a Tumblr blog[2]) that while production of the series began in 2009, he and the staff took the events of 3/11 into consideration when writing the ending. He says, “I think all people on the staff thought about the meaning it has to make a series in the middle of this year 2011.”

The ending of Mawaru Penguindrum offers a hopeful outlook after disaster, having Himari cured of her illness and the city of Tokyo spared from its fiery destruction. In the closing shots, we see child forms of both Shouma and Kanba walking outside of their former house in a scene that parallels two boys in the very first episode. In both instances, the boys make references to Night on the Galactic Railroad (銀河鉄道の夜, Ginga Tetsudou no Yoru), a novel written by Japanese novelist Kenji Miyazawa in 1927. In reference to the novel, the boys insist that death is not the end, but instead the beginning, implying that disaster and trauma should not be obstacles in the way of possibilities. Such events are not blockades, but rather points at which fate is branched and opportunities are born.

Mawaru Penguindrum is a unique healing story full of beginnings and ends, but at the same time suggests a more cyclical nature to life. Ikuhara may imagine the progression of life as a never-ending merry-go-round rather than a direct Tokyo subway line. Themes of rebirth and reconstruction in the wake of disaster are thrust upon the shoulders of these teenagers, reflecting the current climate of Japan’s economic crisis and advocating that a call to action may be needed to divert the course of Japan’s fate. Following 3/11, Mawaru Penguindrum presents the prospect of hope and success with the caveat that its acquisition is not easy and most certainly not free.

At the risk of perpetuating a cliché, Mawaru Penguindrum seems to suggest that the first step to changing fate and progressing forward is reaching out and forming bonds with others, thereby freeing ourselves from our self-imposed social boxes. In other words, love, ambition, and other like emotions are necessary elements, as indicated by the final episode’s appropriate title: “I Love You” (愛してる, aishiteru). If we fail to initiate our own “Survival Strategy,” we will forever remain stagnated, at the mercy of fate and whatever preordained destination it has decided for us.

[1] Anne Allison, “Home and Hope,” in Precarious Japan. Anne Allison (Durham and London, Duke University Press, 2013).

[2] http://natori-umi.tumblr.com/post/23541385459/mawaru-penguindrum-guide-book-interview-with-kunihiko

Thank you for posting! I’ve love the anime, but some things have eluded my understanding (despite rewatching it). Your three posts really clarify some things.

Fantastic article! You certainly have a real knack for writing!

That was a beautiful essay, I was depressed about the series but now i’m better, its one of those shows thats so deep I wouldn’t want to watch it more than once because at that point of find it kind of masochistic, but i’ve always said that the reason I like to watch and honor animes in my own way is because they are a collaboration of artists perspective of the world, and therefore valuable experiences to me for the betterment of my self. but hey gotta hand it to penguindrum, its the first one to make me not beg for more at the end, you have satisfied me, and I thank you for that.

Thanks for writing these three essays. I have only watched the series once a couple years ago, and once in a while I think about what it really means. A lot of it really escaped me and I enjoy reading your interpretations and the research really helps me to understand it in a cultural context. This is a really special anime and it’s great to know it leaves such strong impressions with other people who have watche it too. I hope you have a wonderful day. Thanks!